COVID-19: As if the war was not enough

One year on: stories of hardships, resilience and change in times of COVID-19.

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has affected everyone, everywhere, in one way or another, but not equally: it has hit those living in conflict-affected countries particularly hard.

But what is living through a pandemic really like in places like Iraq, the Philippines, Nigeria, Yemen, the Central African Republic, Colombia, Greece and Azerbaijan, where communities are already struggling with multiple crises and threats? And one year on, what have we learnt on better protecting the communities forced to shoulder the double burden of war and disease?

This comprehensive report, based on real-life experiences documented by the ICRC teams in the field from March to December 2020, shows how the measures taken to contain the pandemic have affected the lives of individuals and communities caught up in conflict.

It also reflects on the lessons learnt, emerging good practice, progressive ideas and strategies put forward by governments, humanitarian organizations and other stakeholders to limit the spread of disease, care for the sick and mitigate the impact of pandemics on vulnerable communities, now and in the future.

Download the full report on the pandemic's complex consequences for vulnerable communities and take-aways for the future.

Here are the stories of Jassim, Joaquin, Falmata, Abobakr, Augustin, Luisa, Jawed and, Sara, and some of what we learned from listening to them, as this crisis presents a compelling imperative for change to more effectively deal with present and future challenges: wars, climate change and the next global pandemic.

- Iraq: Rebuilding a life from ruins

- Philippines: When you are detained, family is everything

- Nigeria: Falmata's wish

- Yemen: The hardest part of being a doctor

- Central African Republic: An orphan's homecoming

- Colombia: I pray my mother will get better

- Greece: We were all suspended in time

- Azerbaijan: What Bahruz would have wanted

Iraq:

Rebuilding a life from ruins

In August 2014 as fighters of the Islamic State group drew closer, Jassim and his family were forced to abandon their homes and settled in the Kurdish north of Iraq as internally displaced people. When the local job market collapsed in spring 2020 due to COVID-19, Jassim made the difficult decision to return home and try to rebuild a life that had been shattered six years earlier.

Read more in the report about this Yazidi family's plight, the interplay between COVID-19 and displacement, the effect of the pandemic on livelihoods and camps for displaced people, the power of cash-based aid to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 and why increasing access to social safety nets makes for good policy during a pandemic.

There were simply no more jobs – none at all. Everything just stopped. If you have to live with nothing either way, it is easier to do so when you are home.

Jassim

Sinjar, Iraq. A man stands in the ruins of his house, February 2019.

Iraq. Members of the Yazidi community flee violence near Mount Sinjar, August 2014.

Mosul, Iraq. Small-business owners in the Old Town register to receive cash grants, November 2020.

Philippines:

When you are detained, family is everything

After being wounded during a firefight between the armed group he belonged to and government forces, Joaquin was taken into custody by police while doctors continued to battle to save his life. He survived severe head injuries against the odds. After COVID-19 began spreading in the Philippines, Joaquin became stranded in a remote police station. His mother managed to remain at his side despite the constraints on family visits.

Read more from the report about Joaquin's life behind bars, how the pandemic affects detention conditions, family life, the pace of the judicial process and prison reform, how new technologies can help address these and broader systemic challenges, and why it proves the truth of the old adage that prison health is public health.

You have to understand. If you're in my situation, your family is all you've got.

Joaquin

Manila City Jail, Philippines. Maintaining physical distance as a preventive measure against COVID-19 is a major challenge in detention, March 2020.

Quezon City Jail, Philippines. ICRC staff and guards practice preventive measures at a COVID-19 isolation centre, April 2020.

Nigeria:

Falmata's wish

Over 100,000 people are currently packed into Dikwa's urban centre, a town in Nigeria's conflict-affected Northeast. Falmata works as a traditional birth attendant in Dikwa and wants her community to respect COVID-19 preventive measures, but she explains that given the situation they face, doing so is a daily struggle.

Beyond her concerns for the health of her community, her account tells us more about managing water and resources, the nexus between humanitarian work and development, and the relation between international humanitarian law and pandemic preparedness.

Few people deny that the virus poses a threat, but we have more pressing problems. The virus is not the only thing we have to worry about. My wish is that we get this vaccine quickly here in Dikwa.

Falmata

Borno state, Nigeria. Mothers attend an information session at Biu General Hospital on complementary feeding for malnourished children, November 2020.

Yemen:

The hardest part of being a doctor

Abobakr is a young doctor in the southern Yemeni town of Aden who volunteered to help COVID-19 patients. He and his colleagues have to fight off rumors, including that doctors in hospitals would be giving COVID-19 patients lethal injections, and deal with the violence that such misinformation can trigger against health workers.

Read in the report what a physician on the front lines of the pandemic tells us about resilience in the face of death, the stigma attached to working with COVID-19 patients, violence against health care and the importance of trust between health-care providers and the communities they serve.

The stigma that comes with this job is one thing – I have got used to it. But being attacked for my work, this I cannot accept.

Abobakr

Sa’ada, Yemen. Children play football against a backdrop of destroyed houses, 2019.

Sana’a, Yemen. A health worker disinfects a market street amid concerns over the spread of COVID-19, April 2020.

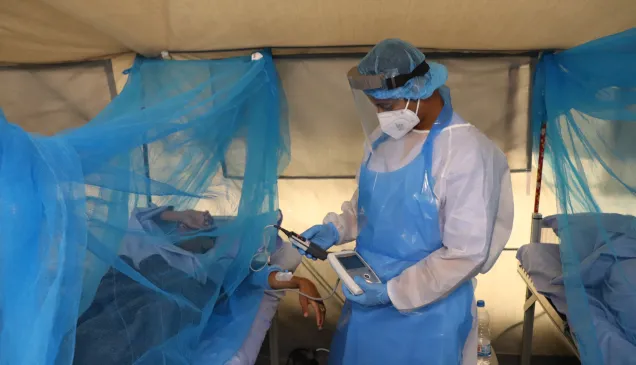

Aden, Yemen. Health staff at the Red Cross COVID-19 Care Center checking oxygen levels on a patient, November 2020.

Download the full report on the pandemic's complex consequences for vulnerable communities and take-aways for the future.

Central African Republic:

An orphan's homecoming

Augustin was 5 years old when he fled his home after both his parents were killed in 2013 following a violent insurgency in the Central African Republic and sought refuge in the Republic of the Congo where he was raised by a foster family. As after years he was finally about to be reunited with his grandfather in early 2020, the advent of COVID-19 in the region triggered border closures, lockdowns, a driving ban and other restrictions, making this reunion impossible.

Read from the report about Augustin's return home to the Central African Republic, how COVID-19 has kept families apart, increased suspicion of foreigners, shuttered schools and put children at greater risk, but also how, with patience and perseverance, happy endings may prevail regardless.

One morning, the lady from the Red Cross told me that my return home would have to be postponed because there was a new disease and the government did no longer allow people to travel. I cried a lot that day, I was just very sad.

Augustin

Bangui, Central African Republic. National Society volunteers promote COVID-19 preventive measures with community mobilizers, April 2020.

Central African Republic. A mother signs paperwork during a family reunification, February 2020.

Central African Republic. Family members surround Augustin on the day of his return home, December 2020.

Colombia:

I pray my mother will get better

The Ramirez and Alvarez families fled their village after a bloody attack against their homes by two gunmen from the armed group operating in their area, killing the heads of both families. They had fallen victim to the aggressive curfew-enforcement tactics employed by some armed groups across Colombia who declared a "military target" anyone breaching the new rules aiming to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic from spreading.

Read in the report how these violent deaths illustrate the pandemic's impact on communities living in areas under the influence of certain non-state armed groups, the need to protect civilians and respect international humanitarian law, and the importance of neutral, independent and impartial humanitarian action in hard-to-reach areas.

It's not fair. My father and my mother had done nothing wrong. Why did they do this to us? We weren't sick from the virus, we were no risk to anyone. Why kill us?

Luisa

Quibdo, Colombia. Hygiene materials are distributed as part of a COVID-19 prevention campaign, July 2020.

Colombia. With the ICRC’s facilitation, a civilian is released after being held by an armed group, June 2020.

Greece:

We were all suspended in time

Jawed, his sister and his aunt left Afghanistan in January 2019, as continued fighting and insecurity made life increasingly unsafe for civilians. They set off on a long journey through Iran and Turkey to end up at Moria on the Greek island of Lesbos. When COVID-19 reached the island, all interviews and procedures linked to asylum claims were frozen. The camp got locked down, shutting in 12,000 people with the virus.

Through Jawed's account, the report sheds light on the protection of migrants in camps and detention centres during the pandemic; access to state-run health-care and social protection systems; border closures, "push-backs" and the right to seek asylum under international law; and the need for solidarity in a global health crisis.

We survived years of war in our home country, a near shipwreck when crossing over from Turkey, and now a worldwide pandemic while locked into a refugee camp, so I guess life can only get better, wouldn't you agree?

Jawed

Lesbos, Greece. A rescue team from the Hellenic Red Cross assists migrants who have crossed from Turkey.

Lesbos, Greece. Migrants flee with their belongings from a fire burning at Moria, 9 September 2020.

Azerbaijan:

What Bahruz would have wanted

Sara's mother lost two brothers without being able to properly say goodbye. One went missing during hostilities over Nagorno-Karabakh in the 1990s and another died last year amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Sara speaks of the sadness and a sense of guilt as sanitary restrictions made it impossible to administer to their deceased relative the proper last rites of Islam and deprived the family of a proper funeral.

Read from the report how their grief speaks to the impact of the pandemic on traditional burial rites and practices, protecting the dignity of the dead during an emergency, the global mental health crisis triggered by COVID-19 and the silent suffering of the families of people gone missing owing to conflict.

It was strangely soothing to watch these videos. It looked like a real funeral – sad surely, but also gracious and caring. I knew that these images would also help my mother once I showed them to her.

Sara

Terter, Azerbaijan. A woman in the ruins of her home, which was exposed to shelling during recent fighting, September 2020.

Sabirabad, Azerbaijan. Sara in front of the grave of her uncle Bahruz, March 2021.

Download the full report on the pandemic's complex consequences for vulnerable communities and take-aways for the future.